After the Festival: Exploring Moai and Experiencing Curanto and Hoards of Horses on Easter Island

In creating the second part of our Easter Island blog, Leslie asked Helen if she’d write a few paragraphs on moai. Helen, a past tour guide on Rapa Nui, graciously accepted. Her discussion follows, and is accompanied by numerous photos when you click on the key moai picture of Ahu Tahai at sunset.

What are Easter Island moai? Moai literally means statue; over 1,000 have been cataloged on the island. Some are buried, some are practically gone, a testimony to wind, rain, and lichen. Most of the moai are phallic representations of the most important male members of each tribe, carved from compressed volcanic ash (tuff) found at Rano Raraku cone. There one observes 397 statues in every phase of construction carved some 1000 years ago with crude basalt tools called toki. The fine featured, fragile moai were then placed upright on basalt ceremonial platforms known as ahu. Occasionally large red scoria cylinders, pukao, crowned the statues’ heads. Amid feasting and rituals, eye sockets were carved and eyes of coral and obsidian/red scoria set in place. The statues were endowed with mana, a supernatural power which enabled them to protect the villages they faced from hostile neighbors.

The largest moai that was successfully moved from Rano Raraku to its intended ahu weighs 82 tons. How did stone age workers move fragile moai up to 14 miles? According to the islanders, they “walked with the help of mana from the chiefs”. It is awfully hard to imagine pulling a 50 ton rock that is more than 5 times taller than it is wide over hill and dale for 10-20 kilometers. There’s evidence that transport became a major problem as statue size escalated – up to 165 tons – in a carving frenzy. The pukao (a minor mystery, though a heavy piece of rock) may simply have become a form of increasing the height of a statue without moving the weight in a single piece. Or pukao may represent topknots of hair or hats.

Although the first European ships recorded seeing moai upright, later ship logs show all moai had been knocked over as perhaps a testimony to intertribal warfare caused by overpopulation, a dwindling food supply, unfavorable working conditions, and the realization that the moai had failed to protect them from death and disease brought by the Europeans.

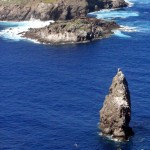

Our visit to the ruins of Easter Island ended with a visit to the ceremonial site at the top of Volcan Rano Kau. This site became the center of culture and power after internecine warfare destroyed almost all the Moai and the culture they represented. What replaced the monumental rocks was swimming to collect bird eggs. What a change! Here we looked down (way, way 300 m down) to the sea and two little islands. Each year strong men competed to win the control of the population for the following year. The competition: climb down the cliff, swim 1 km to the rocks, find the first of the spring seabird eggs (Sooty Terns), swim back with the egg, climb the cliff — You are the Winner!

Curanto, a Culinary Coup:

Mahani invited us to an island picnic, and the highlight was watching Hotu, a very energetic camper/guest/sea urchin-gather/chainsaw-handler prepare a traditional dish which has roots in Polynesia using earth ovens. We thought that the main meal for the picnic was over when we had enjoyed ceviche, grilled chicken and fish (one of the kids proudly arrived from the shore with a strange-looking trumpet fish which was promptly placed on the grill along with the other fish), and salads, plus some powerful pisco sours. Hangu was strumming his guitar and singing a variety of American folk tunes when a very loud chain saw was heard in the background.  Our curanto-creator was beginning to make a classic Chilean dish by cutting up wood he’d found nearby! First a hole was dug in the ground, and then stones were placed inside, followed by a stack of neatly-piled and freshly-cut wood. A fire was lit and the stones were heated until they began to crackle. Later, some of the stones were pulled out and the previously-prepared foil-wrapped beef and fish (which had been wrapped in a banana leaf and exquisitely tied) were placed with hot stones below and above, followed by layers of torn banana leaves. Then a special canvas cover was placed over the whole works. Finally, dirt was piled on top of the cloth covering, and the whole thing was left to cook. Traditionally it simmers for 2 hours or so, but our curanto took much longer. Unfortunately, Mahani, Hangu, Val and Leslie had to leave around 9 p.m., but our house mates, Manuel and Gonzolo stayed until 1 a.m., when the dish was finally served. Reports at noon the next day were of a delicious repast…..well worth waiting for.

Our curanto-creator was beginning to make a classic Chilean dish by cutting up wood he’d found nearby! First a hole was dug in the ground, and then stones were placed inside, followed by a stack of neatly-piled and freshly-cut wood. A fire was lit and the stones were heated until they began to crackle. Later, some of the stones were pulled out and the previously-prepared foil-wrapped beef and fish (which had been wrapped in a banana leaf and exquisitely tied) were placed with hot stones below and above, followed by layers of torn banana leaves. Then a special canvas cover was placed over the whole works. Finally, dirt was piled on top of the cloth covering, and the whole thing was left to cook. Traditionally it simmers for 2 hours or so, but our curanto took much longer. Unfortunately, Mahani, Hangu, Val and Leslie had to leave around 9 p.m., but our house mates, Manuel and Gonzolo stayed until 1 a.m., when the dish was finally served. Reports at noon the next day were of a delicious repast…..well worth waiting for.

Horses on Rapa Nui (Easter Island):

There was excitement when we saw our first horse in the town of Hanga Roa – a teen with ear phones came sauntering on a handsome stallion, passed a policeman near the shore, and “parked” his horse at a restaurant. We saw horses all over the island: on ridge lines near unofficial archaeological sites, in pastures on our long walk from Mahani’s land to town, drinking at the lake of the crater of Rano Raraku, and, unfortunately, having an unpleasant olfactory experience of smelling a dead horse near Te Pito Kura, which some think is the “Navel of the World” with its large round rock surrounded by four smaller ones. We visited Tahai at sunset one night, and were thrilled to see four teenagers on horses come thundering in near the moais, and then turn and gallop out at breakneck speed. We enjoyed seeing this scene repeated 3 more times.

Horses were first brought to Easter Island by Catholic missionaries at the end of the 19th century. Helen reports that when she lived on the island from 1985-1992, horses were sometimes eaten, disappearing into the cooking pot and turned into horse empanadas. Today their numbers (approx. 6000) are larger than the human population (around 5000) of the island. There are so many near the roads that a driver has to be constantly on guard so that he doesn’t hit one. A few are rented to tourists, but most are free to roam unchecked, identified only by the owner’s brand. Their hooves can cause obvious damage to archaeological sites; note our photo of a horse near Ahu Tongariki. Finally, we walked on many trails, trying to avoid stepping in the horse poop. So…., we are wondering if the horse situation is a little out of control, and whether they will eventually have to be culled or controlled in another manner.

We’re return to the northwest part of Chiloe Island tomorrow, and will report on our volunteerism in the next blog entry.

Ines Purcell

28 Feb 2012Hi Leslie and Val. I have the information you wanted, please give me a call.

Regards,

Ines